THE SUMMER sun is falling soft on Carbery’s hundred isles,

The summer sun is gleaming still through Gabriel’s rough defiles;

Old Innisherkin’s crumbled fane looks like a moulting bird,

And in a calm and sleepy swell the ocean tide is heard:

The hookers lie upon the beach; the children cease their play; 5

The gossips leave the little inn; the households kneel to pray;

And full of love, and peace, and rest, its daily labor o’er,

Upon that cosy creek there lay the town of Baltimore.

A deeper rest, a starry trance, has come with midnight there;

No sound, except that throbbing wave, in earth, or sea, or air! 10

The massive capes and ruin’d towers seem conscious of the calm;

The fibrous sod and stunted trees are breathing heavy balm.

So still the night, these two long barques round Dunashad that glide

Must trust their oars, methinks not few, against the ebbing tide.

Oh, some sweet mission of true love must urge them to the shore! 15

They bring some lover to his bride who sighs in Baltimore.

All, all asleep within each roof along that rocky street,

And these must be the lover’s friends, with gently gliding feet—

A stifled gasp, a dreamy noise! “The roof is in a flame!”

From out their beds and to their doors rush maid and sire and dame, 20

And meet upon the threshold stone the gleaming sabre’s fall,

And o’er each black and bearded face the white or crimson shawl.

The yell of “Allah!” breaks above the prayer, and shriek, and roar:

O blessed God! the Algerine is lord of Baltimore!

Then flung the youth his naked hand against the shearing sword; 25

Then sprung the mother on the brand with which her son was gor’d;

Then sunk the grandsire on the floor, his grand-babes clutching wild;

Then fled the maiden moaning faint, and nestled with the child:

But see! yon pirate strangled lies, and crush’d with splashing heel,

While o’er him in an Irish hand there sweeps his Syrian steel: 30

Though virtue sink, and courage fail, and misers yield their store,

There ’s one hearth well avenged in the sack of Baltimore.

Midsummer morn in woodland nigh the birds begin to sing,

They see not now the milking maids,—deserted is the spring;

Midsummer day this gallant rides from distant Bandon’s town, 35

These hookers cross’d from stormy Skull, that skiff from Affadown;

They only found the smoking walls with neighbors’ blood besprent,

And on the strewed and trampled beach awhile they wildly went,

Then dash’d to sea, and pass’d Cape Clear, and saw, five leagues before,

The pirate-galley vanishing that ravaged Baltimore. 40

Oh, some must tug the galley’s oar, and some must tend the steed;

This boy will bear a Scheik’s chibouk, and that a Bey’s jerreed.

Oh, some are for the arsenals by beauteous Dardanelles;

And some are in the caravan to Mecca’s sandy dells.

The maid that Bandon gallant sought is chosen for the Dey: 45

She’s safe—she’s dead—she stabb’d him in the midst of his Serai!

And when to die a death of fire that noble maid they bore,

She only smiled, O’Driscoll’s child; she thought of Baltimore.

’T is two long years since sunk the town beneath that bloody band,

And all around its trampled hearths a larger concourse stand, 50

Where high upon a gallows-tree a yelling wretch is seen:

’T is Hackett of Dungarvan—he who steer’d the Algerine!

He fell amid a sullen shout with scarce a passing prayer,

For he had slain the kith and kin of many a hundred there.

Some mutter’d of MacMurchadh, who brought the Norman o’er; 55

Some curs’d him with Iscariot, that day in Baltimore.

The Sack of Baltimore took place on 20 June 1631, when the village of Baltimore, West Cork, Ireland, was attacked by Algerian pirates from the North African Barbary Coast. The attack was the biggest single attack by the Barbary pirates on Ireland or Britain. The attack was led by a Dutch captain turned pirate, Jan Janszoon van Haarlem, also known as Murat Reis the Younger. Murat's force was led to the village by a man called Hackett, the captain of a fishing boat he had captured earlier, in exchange for his freedom. Hackett was subsequently hanged from the clifftop outside the village for his conspiracy.

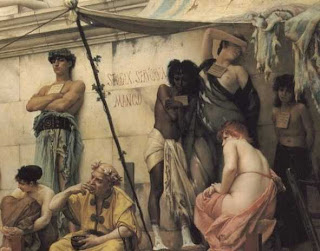

Murat's crew, made up of Dutchmen, Algerians and Ottoman Turks, launched their covert attack on the remote village and they captured 108 English settlers, who worked a pilchard industry in the village, and some local Irish people. The attack was focused on the area of the village known to this day as the Cove. The villagers were put in irons and taken to a life of slavery in North Africa. Some prisoners were destined to live out their days as galley slaves, while others would spend long years in the seclusion of the Sultan's harem or within the walls of the Sultan's palace as laborers. At most three of them ever saw Ireland again.

Conspiracy theories abound relating to the raid. It has been suggested Sir Walter Coppinger orchestrated the raid to gain control of the village from the local Gaelic chieftain, Fineen O'Driscoll. It was O'Driscoll who had licenced the lucrative pilchard industry in Baltimore to the English settlers. In the aftermath of the raid, the remaining settlers moved to Skibereen.

This poem was written by Thomas Osborne Davis (1814-1845) in Victorian style that describes Jansen's raid on the village of Baltimore, Ireland. It was published by Edmund Clarence Stedman, ed. (1833–1908). A Victorian Anthology, 1837–1895 (1895).